Taylor Murrow writes about Shawne Major’s mixed-media assemblages, currently on view at the Isaac Delgado Fine Arts Gallery.

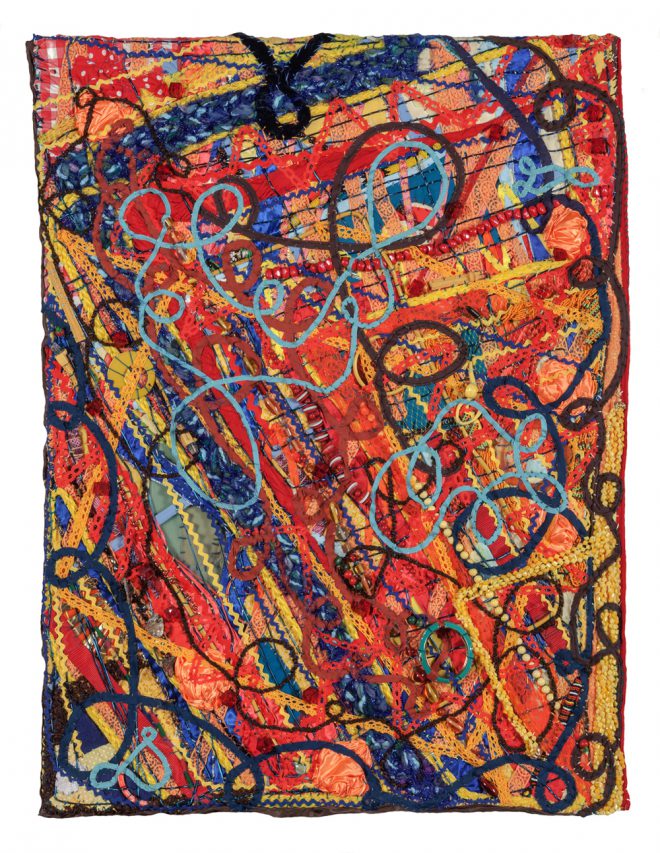

SHAWNE MAJOR, ZENITH, 2017. MIXED MEDIA INCLUDING RIBBON, ROPE, PLASTIC TOYS, COSTUME JEWELRY, STRING LIGHTS, PLASTIC GRAPES, PHONE CHARGERS, A HAMMOCK, ELECTRICAL CORDS, AND A BRAID, HAND-SEWN ON FABRIC AND WINDOW SCREEN. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND CALLAN CONTEMPORARY, NEW ORLEANS.

Shawne Major’s creations are abstract wonders, landscapes of familiar objects sprawled over fabric bases in raucous, colorful patterns and textures. Baubles and toys, rope and ribbon, string lights and electrical cords are all collected in elaborate tapestries. Her pieces take on the appearance of topographical maps, with objects sewn together in layers, and each can take months or years to construct.

Major started her career as a painter but began incorporating objects into her work when she realized the personal and emotional significance they can carry. “I envision these as filters,” Major said to the crowd at the opening reception for her latest show, “Side-Eye” at the Isaac Delgado Fine Arts Gallery at Delgado Community College. We all carry our own filters with us in everyday life, filters through which we view the world. Don’t we sometimes see what we want to see, for better or for worse? It’s not unlike the act of engaging with art, in which each person brings a specific set of experiences that may influence whatever meaning one derives from the artwork.

This is especially true with abstraction, and Major’s use of ordinary, kitschy objects only enhances that feeling. While viewing one piece titled Surface Tension, 2015, in which shapes and patterns are repeated in dizzying formation with bracelets, beads, jewelry, and more, I found myself captured by one particular object: a spinning wheel from a board game. I instantly remembered playing that game as a child—The Game of Life, actually—and was overwhelmed with nostalgia. Soon, I saw other bits of my childhood in the costume jewelry and ribbon on the same piece. For me, the experience of each work was evocative, even when I couldn’t articulate what exactly it brought up in me. I can imagine someone else imbuing other meanings, carrying other filters of experience. Perhaps Major herself put it best that evening: “Abstraction takes you to an emotional or spiritual level that representation can’t.”

SHAWNE MAJOR, PERIAPSIS, 2017. MIXED MEDIA INCLUDING FABRIC, COSTUME JEWELRY, PLASTIC PRODUCE NETS, PLASTIC ROPE, AND FABRIC TRIM, HAND-SEWN ON PLASTIC POULTRY NETTING. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND CALLAN CONTEMPORARY, NEW ORLEANS.

The name of the show, “Side-Eye,” is a playful nod to these referential modes of communication in everyday life. A side-eye can be a biting look of disapproval or skepticism, but it’s also a less direct means of addressing something. Many of the works’ titles also refer to the ways we relate to others, physically or mentally. Aphasia, 2015, refers to the loss of the ability to speak or understand language, due to brain injury or disease. In this piece, ribbon and rope cross in rigid pathways like a circuit board. The color red screams through like a distress signal. Periapsis, 2017, is the point when an orbiting object is closest to the object around which it is traveling, and this work is dizzying in its movement, an exhilarating storm of twisting, curling lines. Maelstrom, 2012, lives up to its name in a terrifically beautiful explosion, a slew of stuffed animals and plastic toys caught in a web of countless cords, ribbons, and even doll hair. An oxygen mask pokes out in one corner, and I almost felt like I needed to pull it out to take a breath.

A cursory glance at one of her works might lead the viewer to believe that Major embraces the random, the arbitrary. But in reality, each wall hanging transfixes with deliberate pattern and repetition, which appear like winding rivers and rock formations. Up close, one can see the labor of each individual hand stitch. Taken in from several feet away, one easily comprehends the greater design. In Major’s process, there might not be a perfectly dictated plan from the get-go, but each part does eventually take its place within the whole. Someone in the gallery the evening of the opening asked how Major decides when a piece is complete. “I just know,” she said. “When I can’t stand to look at it anymore.”

SaveSave